Protecting amphibians for our planet

Protecting amphibians for our planet

- posted on: June 2, 2021

- posted by: Rebecca Jordan

"*" indicates required fields

This post was written by Ciara Gormley, UCBI Intern.

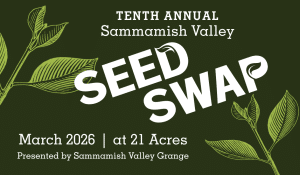

Hi! My name is Ciara Gormley and I’m a Landscape and Restoration Intern here at 21 Acres. I became a part of this work via the Undergraduate Community Based Internships program (UCBI) at the University of Washington, which partners UW students with Seattle-area nonprofits.

I came into this position without knowing a lot about biodiversity or farming, though I have a passion for mitigating climate change. My supervisor, Jess, showed me around the campus, and we looked specifically at the wetland areas of the farm, which are currently in the process of being restored. Wetlands are an important component of the work we’re doing here at the farm, teaching us valuable lessons about the importance of biodiversity, preserving natural habitats, and tracking the impact of climate change on our natural landscapes.

I had never really made the connection between biodiversity and restoration work with agriculture, but as I dove into research, papers, studies, and the science of it all, I learned a lot about just how interconnected these systems really are. We ultimately decided that the goal of my project would be to research, document, and share what I’ve learned, as well as begin discussing how we can best support the habitats of the wildlife we have on our property, and hopefully provide a model for other Washington State wetlands to monitor and improve their ecosystem health as well.

What is biodiversity and why is it important?

Biodiversity refers to the variability in species among organisms of all types in ecosystems, and is vital to healthy habitats, both managed and wild. Essentially, the more types and number of species living in a habitat, the better.

Globally, the state of biodiversity is endangered. In 2019, the UN put out an alarming report finding the rate of species extinction is hundreds of times faster than any other period in the last 10 million years. Over a million species are in danger of extinction, and millions of animals face habitat insecurity. In agriculture specifically, unsustainable practices such as monocropping, use of toxic chemicals, extreme land transformation to accommodate crops, and more are contributing significantly to this species loss.

But that doesn’t mean people aren’t actively implementing solutions and paying more attention to mitigating this species loss. Increasing and aiming for biodiversity is key to keeping habitats healthy and productive, including on farms. Small farms have known this for a long time–that leaving some parts of the land to be wild, biodiverse, and respectful of the life there can improve crop yields and ensure the land remains healthy and productive. To back up what we know anecdotally to be true, scientists have found that species richness increased with natural and semi-natural habitats on farms, and has a positive correlation with crop diversity and production, as well as a negative correlation between pesticide use and species diversity. Farms can play a unique role to increase biodiversity worldwide, and small farms like 21 Acres provide a model of how to sustainably implement agriculture and landscape restoration side-by-side.

All this ties into the central goal of what we’re trying to accomplish at 21 Acres: agroecology, which broadly speaking, is the practice of farming in tandem with the land, environment, community, and people. Agroecology is a movement started by and for small farmers around the world and originated as a way for them to take power back into their own hands in a world of powerful agro-industry influences. It is a concept we are continually trying to implement and improve here at 21 Acres, and one way we can do this is by restoring for and keeping track of the biodiversity on the farm.

Biodiversity at 21 Acres: A Case Study

So what are we aiming for when it comes to species diversity on the farm? Our wetlands specifically make up the bulk of our natural and non-agricultural spaces on campus, and they also serve many important roles, such as helping keep our water clean, improving water flow, and keeping our soil fertile. They also serve as an important habitat for many indicator species, which are specific plants and animals that, depending on their presence, numbers, and health, can tell us a lot about the health of the land. For my research, I wanted to focus mainly on animal indicator species, specifically which ones would be able to tell us the most about the farm if we found them in our wetlands.

I dove into the research, and found lots of papers, articles, studies, and videos discussing how to determine, measure, and restore wetlands and improve biodiversity. I eventually focused on the idea of “indicator species” — or animals that tell us a significant amount about the health of the habitat being studied. However, I was surprised to see that there wasn’t really any predetermined list of indicator species for our types of wetlands, so I’d have to create one myself. I found that while all animals have their role in the environment, one animal group came up again and again when it comes to habitat health and susceptibility to climate change, so much that I eventually decided to narrow my focus to it: amphibians. Amphibians are cold-blooded vertebrates, including frogs, toads, newts, and salamanders, and around the world, almost 40% of species are endangered. Many amphibians thrive specifically in wetlands, but they’re also extremely susceptible to habitat changes. Their life cycles necessitate plenty of access to both freshwater and some access to land and diverse vegetation. Since they’re cold-blooded, their internal body temperature depends on the temperature of their surroundings, so drastic climate changes and habitat loss can pose a very real and immediate threat. They also provide an important food source to many mammals, snakes, and fish, and keep some insect and small fish populations in check. This is why restoring habitat and knowing how amphibian-friendly our preserved areas are is so important: because their presence (or lack thereof) can tell us a lot about the biodiversity across the food chain, and the overall health of our land.

Protecting amphibians for our planet

When looking specifically at amphibians, a few specific ones caught my eye, either for their endangered status or general importance to Pacific Northwest habitat. These include the Northern red-legged frog, Oregon Spotted Frog, Western toad, and Pacific Tree Frog. Some of these species, like the Oregon Spotted Frog, are on the precipice of being extinct, so building habitat with their needs in mind could benefit their population as a whole. Others, like the Pacific Tree Frog and Northwestern Salamander, are native to the Pacific Northwest, and their ability to thrive on our farm would indicate our wetlands are providing a safe, hospitable place for a variety of native plants and animals. When we focus on restoring for these creatures, such as ensuring they have plenty of cool, fresh water and land access with food supply, we will also indirectly be restoring for many other creatures, and providing habitat up the food chain.

At 21 Acres, we’re always seeking ways to improve the processes on our farm and provide a working model of sustainable agriculture, and restoring our wetlands and non-agriculture spaces is just one way we can do this. While restoring for amphibians, we are supporting critical species in changing climate, and benefiting broader knowledge of these species in the greater Seattle area. Personally, learning about how such small creatures play such a pivotal role in healthy ecosystems has been fascinating, and I’m excited to share these findings with the 21 Acres community!

If you want to learn more about amphibians and ways to get involved with citizen science, check out these resources below.

The National Parks Service talks about the relationship between amphibians and wetlands:

https://www.nps.gov/im/gryn/amphibians.htm

Living with Wildlife: Pacific Tree Frogs, their lifecycle, habitat, and more:

https://wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/living/frogs

Learn more about/get involved with the Amphibian Monitoring Program at the Woodland Park Zoo:

https://www.zoo.org/amphibianmonitoring

Learn more about the relationship between biodiversity and farming:

https://sustainablefoodtrust.org/articles/bringing-biodiversity-back-into-farming/

About Ciara Gormley

Ciara Gormley (she/hers) is currently a sophomore at UW studying Industrial & Systems Engineering with a minor in Environmental Studies. She has been interested in environmental issues and climate change from a young age and is passionate about combining environmental justice activism with technological solutions, and figuring out ways to make large scale industries and global systems work more efficiently in a way that incentivizes carbon reduction and empowers people. She’s currently on the 21 Acres campus figuring out what can be done to make the land work better for the farm. She’s using her internship as an opportunity to learn more about agriculture while using her skills to implement positive and productive changes. In her free time she loves to cook, rock climb, hike, and be outdoors.

back to blog overview

back to blog overview