Summer Reading: Perspectives on “Foodopoly: The Battle over the Future of Food and Farming in America”

Summer Reading: Perspectives on “Foodopoly: The Battle over the Future of Food and Farming in America”

- posted on: July 22, 2013

- posted by: 21 Acres

"*" indicates required fields

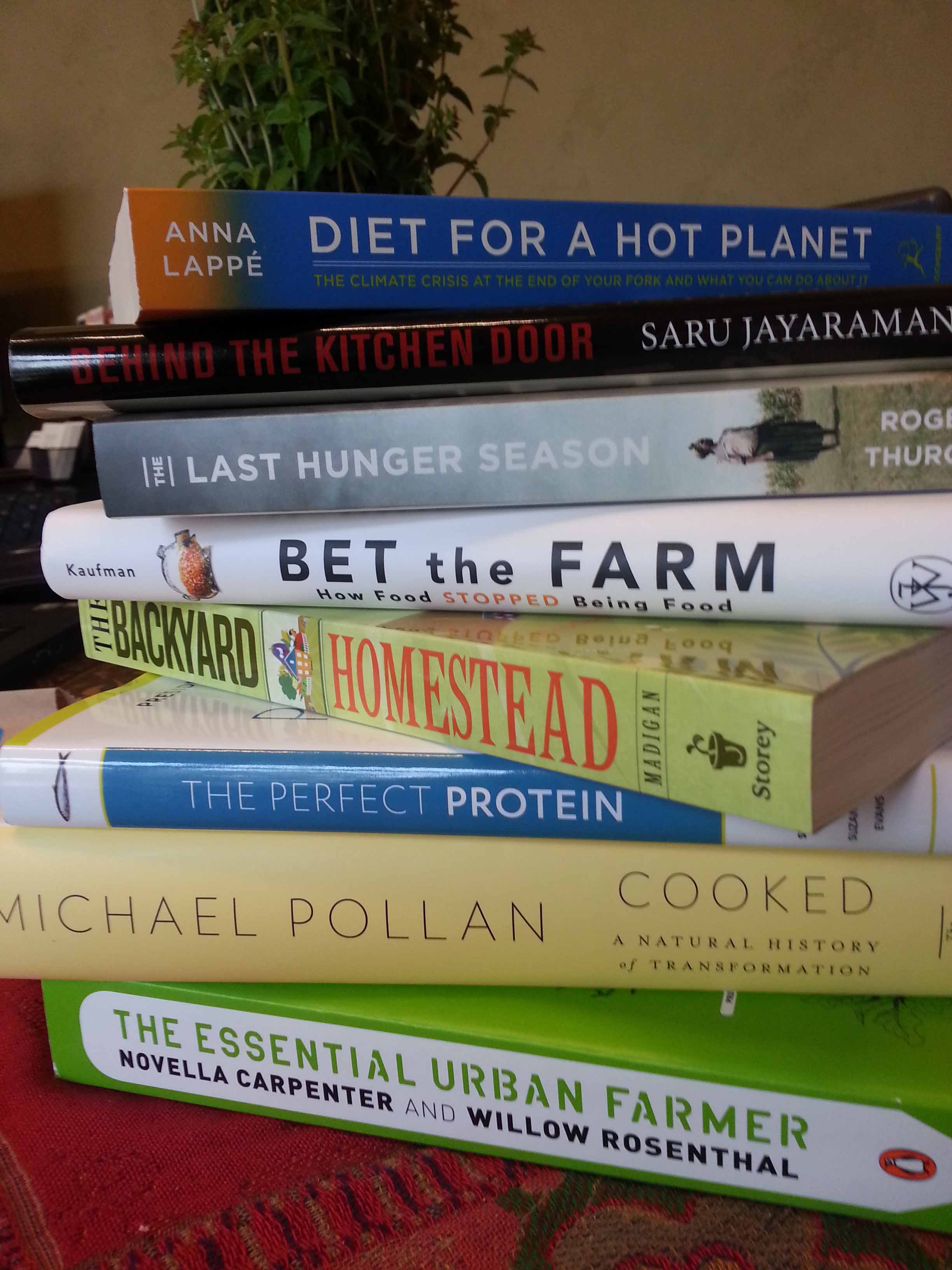

Many of the 21 Acres staff and volunteers were inspired this summer to each take a book from Food Tank’s list of “13 Books on the Food System That Could Save the Environment” and read it and share their thoughts on our blog. Our brilliant and talented summer intern, Johanna Marsh Rayl, is the first to write a blog post and share it here. If you too are so inspired follow this link: http://foodtank.org/news/2013/06/thirteen-books-on-the-food-system-that-could-save-the-environment

In Foodopoly: The Battle over the Future of Food and Farming in America, Wenonah Hauter takes on the task of a researching, analyzing, and addressing the complex and deeply political American food industry. I have long been aware of some of the corporate giants and notorious names; the monsters of the industry like Monsanto, Walmart, Pepsi, and Tyson. What has come to strike me in the first hundred pages of Foodopoloy is that no longer are we dealing with many, strong corporate giants. We are, in fact, looking at one super-monster of an industry where food company directors sit on other food company boards, financial institution boards, nonprofit boards, and in positions of political power, and where the vast majority of the food industry falls into the hands of a few giants with similar goals and political tactics.

Doesn’t this ring a few bells in US history? What happened to the antitrust regulation of the early 1900s that we put into place after the turbulence of the railroad, steel, and oil industries? Hauter covers the history of such regulation, revealing the key players in Reagan-era Washington that helped weaken such legislation and pave the way for today’s situation. Battles were waged throughout the 20th century between farmers’ organizations and politicians. While the New Deal agriculture programs brought periods of prosperity to farmers, post-WWII changes began the weakening of farmers’ voices. The Committee for Economic Development lobbied to move farm workers to industrial jobs while industry was pushed into farming. Through the rest of the 20th century, the food industry became more and more consolidated into today’s few corporations, which exert immense political power thanks to the legislative changes of the previous decades.

Hauter dismisses the common argument that if only subsidies were cut, then we could weaken the industrial monsters of the food industry. While we may weaken them, we will certainly kill off the mid-size family farms that depend wholly on these subsidies. Although the beginning of the book has not yet covered a call to action or solution to our situation, I do know that it will urge the importance of making these mid-size family farms the norm in the American food industry. Foodopoly has been a fascinating and highly informative read so far and I recommend picking it up for anyone who enjoyed Food Inc., anyone who takes an interest in the food industry, anyone who likes US history, and anyone who eats!

— Johanna

back to blog overview

back to blog overview